Introduction

Commercial Enterprise

Cultural Organisations

Media and Representation

Directions for Further Learning

Introduction

In addition to religious institutions and community organisations there were many other support structures that played an important role in the settlement and presence of migrants in Birmingham. Commercial enterprise, social and cultural organisations and the development of minority ethnic media were instrumental in contributing to the sustaining of communities, cultural renewal and challenging representations of black people in the city.

<return to top>

Commercial Enterprise

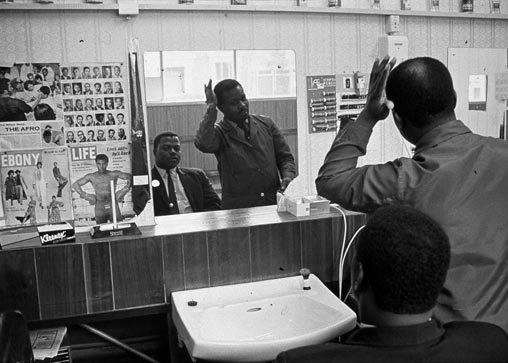

As they settled there were many aspects of the culture and lifestyle from their countries of origin that migrants either consciously or unconsciously preserved. Clothes, diet, furnishings, music, film and literature were some of the material aspects of the distinct cultures that many brought with them and sought to access and replicate in Britain. To meet the demand for the cultural products of 'back home' community enterprises arose wherever groups of migrants were concentrated in an attempt to supply the needs of growing communities. Butchers, grocers, hairdressers, supermarkets, draperies, sweet shops, jewellers and travel agents were among the businesses that developed as Birmingham's community became more culturally diverse.

Shops were a vital space where migrant communities could be consolidated. According to Small (1994) they represented:

"A meeting place, somewhere to go to keep in contact with 'back home,' exchange gossip and share the experience of surviving in a hostile environment. It was where Black people could find out what their rights were, what they were entitled to and also importantly somewhere they could freely speak Turkish, Urdu, Swahili, Patois, Hakka or any of the 200 dialects spoken in their homes without being made to feel guilty." (1994:33)

The development of migrant enterprise in Birmingham led to the city becoming a magnet for migrants in other cities with smaller migrant populations and fewer resources to sustain growing communities. Nirmala Patel, who came to Britain as a teenager in 1966 from Kenya, highlights how her family would travel all the way from Gloucester to buy spices at a shop in Birmingham:

"It used to be called Kim’s, that was the oldest shop that we can remember, probably starting in late ‘50’s and until recently it was there and so we would come once in six months or so to do the shopping. The most difficult thing was not finding a garlic and ginger in things, chilli’s, those things were… because you need fresh every week. We used to have to do with just dry spices and that was very strange." [MS 2255/2/092 p5]

Food in particular, played a vital role in the creation of a sense of home and the maintenance of communal identity. By handing down family recipes through the generations migrants enabled the culture of 'back home' to be sustained. As the dishes were consumed, the life of the country of origin continued however, the new location also meant that the recipes could not remain unchanged but were adapted to suit new environments and palates. As well as the maintenance of culture within migrant families and communities, food also served as a bridge between different cultural traditions.

The development of catering industries provided both new culinary experiences for people in the city and an important source of employment. Within Bangladeshi and Chinese communities in particular the catering trade flourished. In an environment where many migrants experienced barriers in finding suitable work, self-employment or working for the family business provided opportunities for earning a living. Although the work was demanding and relied on the often unpaid labour of family members, catering enabled migrants to carve out a distinct space for themselves in the commercial marketplace. Birmingham's earliest 'Indian' restaurant started out in a café in Steelhouse Lane owned by Abdul Aziz from Gorpur-Jamalpur in India (now part of Bangladesh) (Choudhury, 1993:76). After selling curry and rice at the café as early as 1945, Aziz went into partnership with Afrose Miah and rebuilt the building, turning it into the Darjeeling Restaurant - the first Bangladeshi restaurant in Birmingham.

<return to top>

Cultural Organisations

Organisations were also developed to cater for the social and cultural needs of migrants. When Commonwealth migrants began arriving from the 1950s onwards there were few recreational and social facilities open to them. The operation of the colour bar in pubs, clubs and dancehalls, different cultural norms and practices, and the language barrier meant that the social life of many migrants was limited. Community centres, clubs and societies and arts-based organisations that were subsequently developed helped to consolidate both a sense of community and minority ethnic identity.

Yousuf Choudhury (1993) notes that many Bangladeshi Sylhetis were not able to connect with existing clubs and organisations, as a result of which they experienced isolation and depression. In 1961 a group of young Sylhetis formed a youth association 'Jubo Sangha' at 125 Upper Sutton Street in Aston (Chaudhury, 1993:138). Members made music, sang songs and formed an amateur football team which was managed by the association's chairman Habibur Rahman.

Irish culture has maintained a distinctive presence in the city for many years. The Harp and the Shamrock were two clubs in Birmingham established during the 1950s where the city's Irish community could enjoy socials and traditional Irish dances. The Gaelic League and the Gaelic Athletic Association were revived around the same time, the latter promoting Gaelic games which enabled the more recent Irish migrants to participate in traditional sports such as Gaelic football and hurling. Birmingham's St Patrick's Day parade, which began in 1952, is now the third largest parade in the world and has a significant place in the city's cultural calendar. A gallery of photographs of the 2006 parade can be found in the Photographic Exhibitions section of the website.

<return to top>

Media and Representation

Whilst black political organisations produced anti-imperialist papers for the African diaspora in Britain prior to the end of the Second World War (Benjamin, 1995) it was the post-war period and ensuing years that saw a growth in media activity and the development of what has become known as 'the black media.' Negative media representations were, and continue to be, a feature of everyday life for the growing minority ethnic communities. Stereotyping through sensationalist news items contributed to black people being disempowered by widespread perceptions of them as outsiders and 'the other.' When it wasn't sidelining or misrepresenting the issues, the mainstream media presented limited opportunities for black people to redress the balance from within what was a very white and middle-class establishment. In Britain forms of black media developed as a response to these issues; what it achieved was the creation of a space where black communities could communicate - a place for black voices to be expressed and be heard.

The Gleaner (1951) and the Caribbean News (1952) were two national newspapers that were set up to meet the needs of post-war Caribbean migrants. As well as focusing on issues relating to black people in Britain, they provided an important link with the countries people had migrated from. Both were on opposite sides of the political spectrum and the Caribbean News, which was produced by the Caribbean Labour Congress, was banned in the Caribbean because of its radical left-wing politics. Henry Gunter, the first black representative on Birmingham Trades Council, wrote for the newspaper and was also the West Midlands correspondent of the West Indian Gazette (correspondence with Fiona Tait.) A copy of a Caribbean News article written by Gunter in 1953 entitled 'End Colour Bar in Britain- say workers in Birmingham' can be found in the City Archives [MS 2165].

Newspapers were also created in a range of languages to cater for South Asian migrants whose first language was not English some of which included the Mashriq, Des Pardes, Akhbar-e-Watan and the Daily Jung. The Mashriq ('East') was Britain's first Urdu newspaper which began in London as a weekly in 1961. Mahmood Hashmi, who worked as a reporter on the Mashriq during the 1960s, became editor of the country's first local Urdu newspaper- the Saltley News.

<return to top>

Directions for Further Learning

One way of exploring the cultural change brought about in an area by migration is by looking through trade directories. Taking a particular street, for example part of Soho Road, trace the change in commercial premises over a 10 or 20 year period. What do you find?

<return to top>

Author: Sarah Dar

Main Image: Photograph by George Hallett [City Archives: MS 2249]

<return to top>

|